UK cities have risen up the political agenda. Eleri Jones AoU and Rachel Cooper OBE AoU reflect on how the UK Government Foresight project on the Future of Cities tried to engage policy makers with evidence and tools to help them think about the

long-term future.

Today, half the world’s population live in cities. This will rise to 60 per cent by 2030 and to 70 per cent by 2050. An estimated half a million new people join the world’s cities every week. The UK Government Office for Science’s Future of Cities project looked to 2065 to provide policy makers at national and city levels with evidence, tools and capabilities to make evidence based decisions about the future of UK cities.

The Future of Cities project was one of the most challenging Foresight projects ever attempted. Firstly, due to the breadth of its concerns, any one of the project’s six main thematic areas – Living in the City, Urban Economics, Urban Metabolism, Urban Infrastructure, Urban Form and Urban Governance – could have been a Foresight project in itself!

But in addition to this broad scope, the Future of Cities project initiated a ‘twin track’ programme of City Foresight projects, which were led by cities at the same time as the national project. These City Foresight projects1 were undertaken by different sectors in each place, depending on who took the initiative to apply for a small amount of seed funding made available by the Government Office for Science. To obtain seed funding, City Foresight projects had to consider the long-term future of the city, involve multiple stakeholders and demonstrate a plan to ensure legacy. But it was up to the city as to how this was achieved, the aim being to encourage cities to take ownership and develop a project that would respond most effectively to local interests and needs.

The ‘twin-track’ approach provided the national Foresight project with myriad logistical and analytical challenges. But, it also provided some really unique insights into how Foresight is perceived, developed and utilised at different levels of government – and how Foresight at different governance levels might be better connected in future. Much has changed since the publication of the final project reports in April 2016, but we feel that the imperative to learn from the project’s ‘twin track’ approach is even greater than ever before.

For instance, the EU Referendum result has shown us that there is a clear need for policy makers to be able to effectively understand and connect the aspirations of localities with decision-making processes across different levels of governance. Cities need to be equipped to develop and communicate genuinely sustainable and inclusive visions of the future effectively: their own imperatives and choices. Whitehall meanwhile needs to have methods for incorporating these visions into coherent national policies that create a future that ‘works for everyone’. We want to illustrate, through the lessons learnt from the Future of Cities project, how Foresight activities in the future can work to support these processes, in practice.

Over the course of the three-year Foresight Future of Cities project, 15 academic papers were commissioned to provide national level insights across the project’s six themes, as well as a series of opinion pieces and blogs. Following a seminar tour of 25 cities across the UK and the initiation of the City Foresight projects, the evidence base swelled to include both academic and anecdotal insights at the city level.

Collation of such a diverse evidence base was a first for a Government Office for Science Foresight project and presented an exciting opportunity to engage Whitehall with genuine insights from those grappling with the day-to-day management and development of cities, rather than with academic evidence alone. In a context of devolution, as policymakers came under increasing resource pressures to deliver bespoke ‘Deals’ for multiple cities, this seemed like a winning combination. A city’s statutory strategic plans could be easily accessed through a council’s website, but a well-evidenced vision for the long-term future was not something that most cities produced. This type of thinking would be a unique and insightful output of the City Foresight projects. It would be coupled with high quality, strategic analysis drawn from the academic evidence base and reveal innovative solutions to policy questions, as well as contribute to the development of City Deals. However, as with most visions of the future, there were some unforeseen challenges.

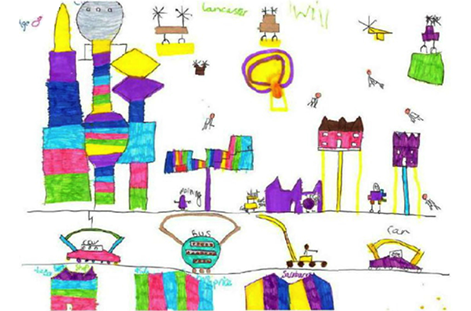

Image reproduced from the Lancaster Future of Cities project. The project encouraged young people to engage in the process of thinking about the future of Lancaster through a drawing/writing competition asking them to imagine their city, Lancaster, in 2065. According to one competition entry, future transport in Lancaster will include jetpacks.

Firstly, it became clear that the evidence base, despite its breadth, depth and diversity, was not going to produce genuinely innovative, new insights about the future of cities that Whitehall could use to take decisions. This seemed utterly counter-intuitive on the face of it. But the multitude of potential policy interests in ‘cities’ across Whitehall made it virtually impossible for the project to address, let alone inform, each specialised interest. For example, policy makers would express interest in hyper-localised insights on health inequalities in Glasgow, which the project had gathered during a visit to the city. But they needed and wanted entire data series on health inequalities across the UK, and the project did not have the resource or capacity to undertake this type of commissioning. The key message which could be drawn from across the evidence, was that Whitehall should think about cities as systems, and as systems of systems, and to recognise the interdependencies inherent in these systems. This, of course, did not relate to any concrete challenge that policy makers were trying to address – it was a framework for holistic reflections about cities generally which didn’t sit easily with the departmental structures and ways of working that are in place and very much ingrained.

Secondly, as the City Foresight reports came through, it became clear that they had largely been about establishing shared challenges, values and aspirations about the future, rather than well-evidenced articulations of how the future of a city was to be delivered. The outputs from the projects often highlighted successes related to achieving consensus about the principles which would guide the future development of the city, and the establishment of new networks to deliver these. Cities often reported that running a Foresight project had helped stakeholders overcome past disagreements, as they found common ground through thinking about the future. In short, the outputs often focused on the process of running a Foresight project, rather than the specific decisions that had been made as a result. The value was seen to be in bringing people together. Young people formed youth chambers, whilst universities, councils and businesses came together to run public art exhibitions about the future of the city. Needless to say, despite the very positive, tangible outcomes, this was not viewed as helpful for decision making purposes in Whitehall, however interesting the artistic outputs might be.

Foresight for cities – lessons learned

So, what can be learned about from this experimental approach to Foresight projects and how might it help cities in the future?

Firstly, as urbanists will know instinctively, cities are about lived experiences – decisions about how people live cannot be arrived at by evidence alone. However, Foresight, when applied at a city level, can support a negotiated process of discussion, engagement, debate and consensus building about the future of cities, which is underpinned by evidence. An excellent example of this is the Milton Keynes 2050 Futures Commission which was run from September 2015-2016, following engagement with the Foresight Future of Cities project2. This process balanced public engagement with academic evidence and expert input to develop a set of principles for the future development of the city. These were unanimously endorsed by all political parties and leaders in the council and the specific recommendations contained in the report are being implemented by a new team of officials.

Secondly, in lieu of a complete overhaul of the departmental structure and ways of working in Whitehall, there is clearly a mode of working that resulted in successful outcomes at both Whitehall and local levels. This is when a common focus brings the two together as demonstrated by the Future of Cities project in late 2015, when it undertook yet another experiment and launched the ‘Graduate Mobility Project’3. In this experiment, the project’s expert evidence base was used by a cross-Whitehall group of senior officials to agree the 10 most pressing challenges for cities in the coming decades, from a national perspective. Whitehall officials selected one challenge for closer examination and local officials were invited to meet with them to present approaches to meeting that challenge from a city perspective. From this, it was possible to see what Whitehall could do to support the many different approaches to the same challenge that were happening across the country. This made engaging with, and acting on, an evidence base across multiple spatial scales, far more achievable and we feel that this provides a template for the future.

The future of cities: visions and networks

If UK cities (large and small) are to show leadership and be places where inclusivity and growth can occur, it will be necessary to unleash creative and innovative thinking about the long-term future and create new networks and partnerships – as well as support (and innovate) traditional statutory planning processes and decision making. What became very clear from the ‘twin-track’ programme is that cities are instinctively keen to think creatively about their long-term future, to create new networks and learn from each other to gain inspiration about how to go about this more effectively.

To respond to this need, the project created the very successful ‘City Visions Network’, which brought together cities to share their approaches to creating future visions and how these could then be used to initiate projects and programmes of work. But how can this be sustained, now that the project is completed and the seed funding and support from the Government Office for Science is unavailable? Of course, there is an important role for Whitehall to support and encourage this type of undertaking – it is certainly in their interests to understand how people across cities are thinking about their future. But it is not clear that Whitehall is best placed to own and drive a network which is ultimately trying to negotiate and facilitate the complex process of integrating and interpreting the aspirations of cities and citizens for the future with nationally driven policy priorities.

We would argue that urbanists can take a lead. In fact, the Urbanism Awards process shares many of the attributes of the City Visions Network; a group of multidisciplinary experts, who are practiced in visioning the future of places, engaging with, and learning from, cities across the UK and beyond. In this way, urbanists are not only well placed to support individual cities in undertaking Foresight projects, but can also take the lead on supporting a national network of people invested in thinking about the future of our cities.

Eleri Jones AoU was the project team leader for the Future of Cities Lead Expert Group and is now an associate at Space Syntax where she leads the Urban Policy and Foresight Team.

Professor Rachel Cooper OBE AoU is distinguished professor of Design Management and Policy at Lancaster University.

This article was written with the help of: professor Sir Peter Gregson, chief executive and vice-chancellor, Cranfield University; Geoff Snelson, director of strategy and futures, Milton Keynes Council; Fiona Robinson, MK Futures 2050 programme manager; professor Mark Tewdwr-Jones AoU, professor of town planning and director of Newcastle City Futures; Oliver Dean, managing director, MK21

For more information visit: gov.uk/government/collections/future-of-cities

1. Links to the final reports from the City Foresight projects can be found in Foresight for Cities, Appendix A, p.51 gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/516443/gs-16-5-future-cities-foresight-for-cities.pdf↩

2. mkfutures2050.com/↩

3. gov.uk/government/publications/future-of-cities-graduate-mobility↩