A crucial aspect of urban design is the social responsibility to engage meaningfully with communities and the public at large, responding to and protecting the interests of society. However, community engagement is not commonly included in urban design course curricula. And with good reason. Dr Lucy Montague AoU reports back on her experience of merging the two.

Whilst we might readily agree in principle with the inclusion of the community in urban design and the inclusion of live projects in built environment education, there are many questions raised by this objective. How should it be done? Is it effective? How can it be resourced? And how on earth do you fit the square peg of community groups into the round hole of academia?

Of course, community planning is far from a new area of debate or practice. There are compelling arguments for a range of approaches to this type of interaction, demonstrating how decision-making powers might be shared amongst the different actors and how the process can be embedded within the local community. The intricacies of achieving effective and meaningful community engagement are well documented. But they strongly suggest that it can be an instrumental achievement that secures not just a more responsive design, but also endorsement from stakeholders. This translates to a sense of ownership within the community crucial to the long-term success for the place/space in terms of occupancy and maintenance.

Yet the idealism of this scenario must be tempered with reality. In current times the goals of communities’ engagement, and the means by which they may be achieved, are particularly challenged by economic constraints impacting on local authority budgets. When the financial and therefore human resources of the public sector are severely diminished, the capacity for urban design guidance is typically virtually eliminated as a non-essential service. Usually, this results in a swell of provision from the voluntary sector, attempting to address the deficit (for example the technical aid movement in the 1980s). Local councils across the UK are suffering extraordinary cuts in their financial resources due to decisions at a national government level. It is in this context that the community engagement module has developed within the MA Urban Design at The University of Huddersfield.

So far £106m has been cut from local government budget in Huddersfield and a further £50m is still to go. In order to continue to provide essential services such as healthcare and education they have been forced to scale back the delivery of non-essential services and develop an entirely different model in which the council has a more indirect role, enabling community groups to maintain or change local spaces. Additionally, one could argue that universities have a civic role to play: engaging with the place within which they are geographically located. In this vein, I speculated on the possibility to simultaneously build the capacity of the university to actively engage with local communities, to address the shortfall of public sector services and to create an unusual learning opportunity for our students.

In at the deep end…

However, as I mentioned earlier, community engagement, and live projects in general, are not commonly integrated into the design curricula. Combining the rigid timetabling restrictions and slow-paced bureaucracy of a university with the unpredictability of live projects and flexibility required to work with community groups leads to a stressful and risky venture. Ultimately, the inaugural alignment of the scheduled module and a live community project pursued this year was achieved by initiating contact with multiple council teams seven months in advance, asking for leads on community groups that may be interested in working with us. One of these teams – The Parks & Open Space Team – was particularly responsive and after many discussions and much correspondence they advertised our skills offer to groups. This generated six formal expressions of interest. I then shortlisted a few who seemed the most appropriate. I talked to each of these in order to better understand their objectives, expectations, how established they are, membership numbers, availability, and level of organisation in order to judge which group would be best for the students to work with. Of course, at each stage this was not a particularly linear process.

One of the groups presented itself as particularly suitable as they were well co-ordinated, had realistic expectations, feasible timing, were geographically accessible to us, and had a project appropriate to the skills set of the students and to the scope and scale of the module. This was a residents’ group in a village outside Huddersfield whose interests focus on improving the quality of their public spaces. Having successfully improved small areas of planting and the state of some of the village’s ginnels (alleys), they sought support with their most ambitious project to date – the re-design of the local park, ‘Two Furrows Rec’.

Their core membership of around 10-15 people, supplemented by up to 40 additional residents who actively participate in one-off events and activities, suggested an adequate yet manageable number for participation. I had extended conversations with the group’s chairperson to test the feasibility and held an initial meeting with the group to establish how they would like to move forward and work with the students. The result was a date and objectives for an evening event with them and an extension, at their request, to include engagement exercises with local school children in the village, as primary users of the space.

Further discussion with the local primary schools led to a programme of several events throughout the module’s duration. In parallel with all these developments, I maintained contact with the council to ensure that they were aware and supportive of our collective endeavours. This also needed to be reported back to the group to alleviate their concerns that this might be an ineffectual exercise. Once this rough plan had formed and the scope of participants identified, I had to rush through ethics approval at the university. At this point, and only at this point, it became possible to partly relinquish control to the students and assume a supervisory role. Ultimately, despite many months of preparation, this timing was tight for the scheduled start of module.

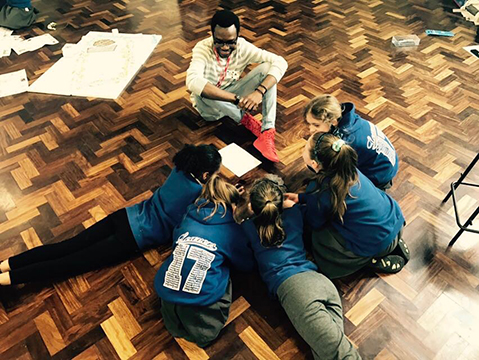

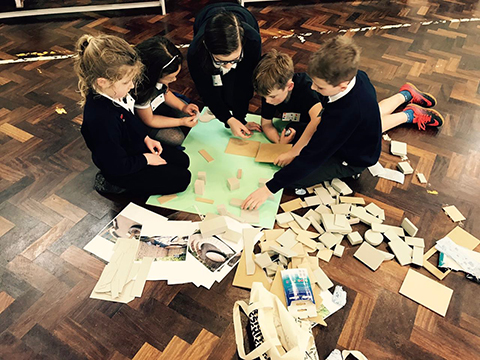

The students worked to plan and deliver four events: three with the schools and one with the residents group. In each instance, weekly tutorials guided the students to consider the objectives of the overall engagement process and therefore each event in order to devise agendas and activities to achieve them. This was done with the consideration of the literature around participation principles, methods and techniques (which the module introduced in parallel through seminars) and others’ experience of communities’ engagement (contributed through guest lectures from speakers giving public sector, private sector and research perspectives). Practical considerations were of course also a factor, especially limitations to both the time available and financial resources. The events were not intended to be radical in their approach but to introduce the students to this type of work, so they included fairly typical exercises covering analytical work, trying to draw out participant’s understanding of the issues with the space, how they currently perceive and use it and generative work in which they responded to precedents, proposed ideas and modelled elements within the design.

A worthwhile endeavour?

Inevitably the results were imperfect due to the complexities of any engagement, the very restricted time available to develop the project and the students’ inexperience. It was also somewhat more demanding than it might have been as it required the students to consider two very different types of participant – the residents’ group and primary age children. There were however several positive outcomes:

- The council has saved resources by using this engagement as the formal consultation for this space required by their review of parks and open spaces prompted by the budget cuts.

- A proposal for the ‘Two Furrows Rec’ has been co-designed with the community, one which they endorse and feel they have ownership of. The community has had far greater input this way and a more tangible output than they would have had as part of the council’s usual consultation process.

- The residents’ group and the local primary schools have been provided with a list of possible funding sources they would each be eligible for that could enable implementation of their design. They also have professional documentation of a design they have developed and endorsed which can be used to support these funding applications.

- The students report a challenging and enjoyable learning experience that has been grounded in theory but also actively introduced them to many aspects of communities’ engagement. Their individual retrospective reflections demonstrate learning that will support their future endeavours.

There were countless opportunities for this endeavour to have had a less positive outcome. Several key factors influenced this. Fortunately, I had constructed the module documents (required over a year in advance of delivery and with external approval for any changes) with a dangerous level of ambiguity that allowed the specific project to be accommodated even though it could not have been known so far in advance and will necessarily change every year (unlike the documentation). Equally fortunately, ethical approval was uncharacteristically quick and forthcoming.

And perhaps most fortuitously the communities’ involvement did not fall through at the last minute leaving me with a project-shaped gap in the module. With extreme advance planning, creative interpretation of academic bureaucracy and acceptance of risk and uncertainty beyond any comfortable level, the square peg of a live community project was hammered into the round hole of academia. It has been complex and time-consuming to set up and manage but the benefits would seem to justify this outlay: not least the temporary creation of a tangible link between the ivory tower of academia and the communities within which we are located, whilst reinforcing the civic role of urban design.

Dr Lucy Montague AoU is a senior lecturer in urban design at the School of Art, Design & Architecture, The University of Huddersfield