ph. Neil MacWilliams via Flickr

Founded in March 2015, the grassroots movement Take Back the City wants London’s future to be in the hands of the many, not just the few. I went along to the group’s September ‘training event’ and had a chat with member Zahra Dalilah about the problem, the objective and what urbanists can do to help.

The story

The political establishment is “letting the people down”, Dalilah tells me; disconnected from the lived experiences of communities. As the epicentre of Britain’s local institutional experimentation, the effects of neoliberal urbanism on London’s neighbourhoods are the central qualm of Take Back the City. The group holds that private property rights and the free market have promoted capital accumulation over the requirements of community, family and home. It points to the institutional legitimisation of wrenching profit from social space, both producing and exploiting socio-spatial difference. There has been, Dalilah suggests, minimal political effort to “make the land for people, not for profit”, as unprecedented levels of displacement and unaffordability plague Londoners.

Meanwhile, the group posits, top-down attempts to empower localities have made no difference, and power remains firmly with the “super-rich and corrupt politicians”. London mayor Sadiq Khan, with his ties to property developers and dubious transport promises is, advocates feel, doing little to address London’s inequalities. The Labour party is busy tearing itself to pieces and Theresa May slips into leadership without a word from the people.

“We need activism based on the everyday needs of communities”, says Dalilah. Our populace is progressive, diverse, full of energy and vitality – we shouldn’t stand for being so poorly represented. Take Back the City holds the simple view that we all have an equal ‘right to the city’, to co-create our urban spaces. It proposes a shift from participative tokenism to delegated power and citizen control; a creative, transparent, open style of democracy.

Take Back the City canvassing ideas for their manifesto

Steadily gaining supporters, Take Back the City began forming a ‘People’s Manifesto’ for London. This involved crowdsourcing the views of over 1,000 Londoners through visits to community groups, including unions, homeless shelters, schools and housing co-ops, as well as receiving online contributions. Dalilah stresses the importance of creative mediums, for example art and poetry, in attracting politically disengaged participants. What emerged were a set of policies “built solely from the needs and wants of every day Londoners”.

I get handed the manifesto at the ‘training event’; a simple paper booklet “stating the obvious”, as Dalilah puts it. Among sections on housing, education, labour, transport and environment, it offers “seven changes we urgently need”. These include rent control, the reintroduction of Education Maintenance Allowances, a compulsory London Minimum Wage of £11 per hour and cutting current transport prices by 20 per cent. Take Back the City sought to campaign for these changes from within the establishment. In the 2016 London Assembly elections, Amina Gichinga, the movement’s powerful public face, ran for the City and East constituency. Dalilah described this as a process of “engaging with the political system from the outside, to demonstrate how different things can be”.

With a crowd funded sum of £5,000, members campaigned hard, directly pitching their message to people on London’s buses, streets and through cultural events. Come May 5th, Amina gained 1,368 votes, apparently tripling expectations. Although amounting to just over 1 per cent of the total, this is a substantial following for a 14-month-old movement. The group’s Facebook page also currently has 3,000 subscribers.

Part of a wider movement?

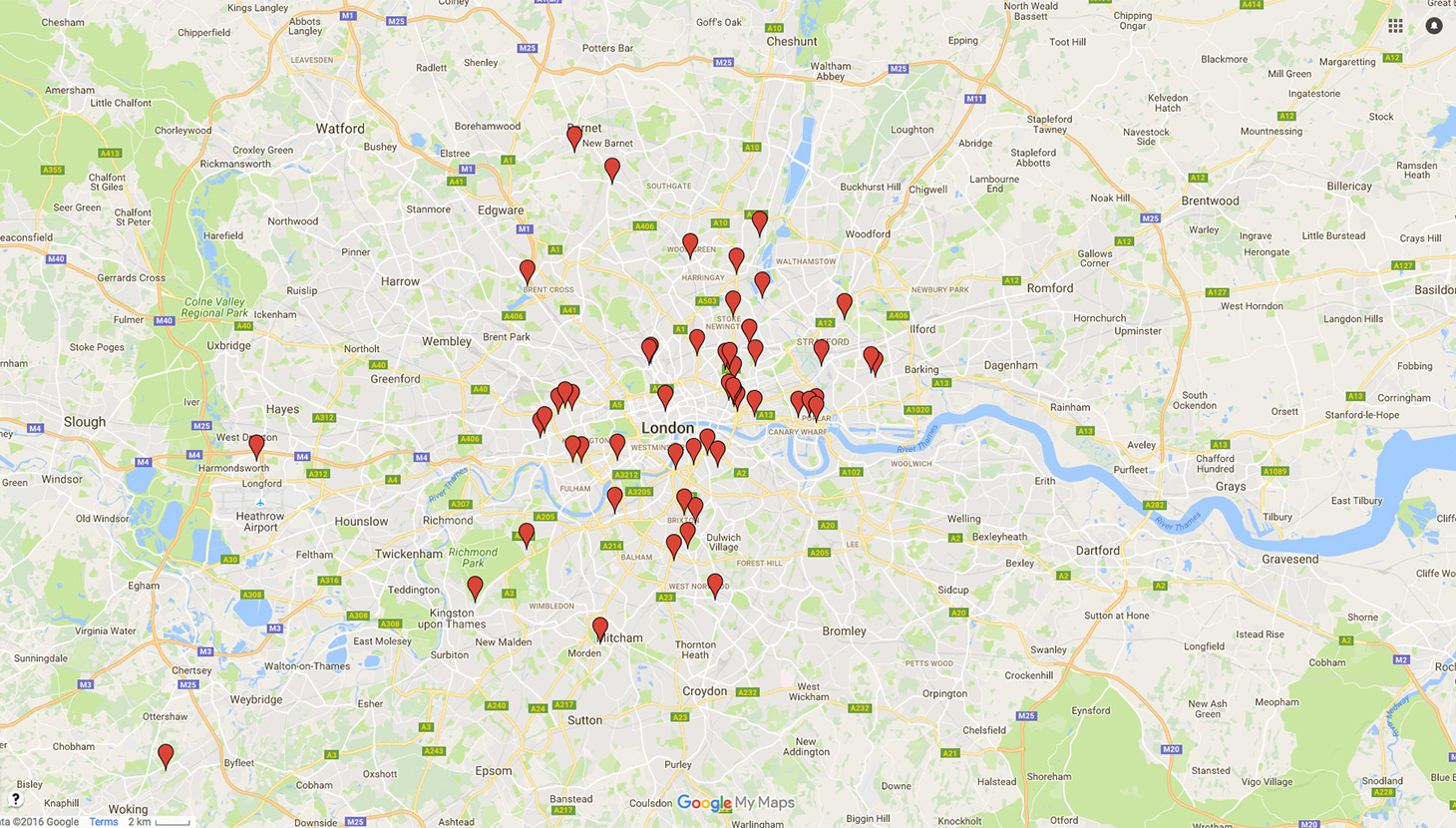

As Harvey’s ‘Rebel Cities’1 delineates, divisive state power and contemporary capitalism must be tackled based on the reality of individuals’ everyday experiences. The workplace no longer provides the main platform for this struggle in the West. Collective action thus revolves around the places in which we live; the insecure city-dweller against privatisation and gentrification. Take Back the City is therefore certainly not alone. The map above, created by Action East End, shows 53 local action anti-gentrification and housing campaigns across London, the majority of which have sprung up over the last few years.

Some of London’s housing and gentrification campaigns, including Save Soho, Aylesbury Estate Occupation, Save Earl’s Court, Hands Off Knights Walk, Save Norton Folgate, and many others. Map ph. Googlemaps

Right to the city-esque movements are also erupting in other cities. Take Back the City’s members talk proudly of the inspiration gained from Spanish citizen platforms, where five years of austerity have shaken the establishment. Ada Colau, founder of a direct action housing group and leader of citizen platform Barcelona en Comú, won Barcelona’s 2015 mayoral election. Colau has promised to “govern by obeying the people”. Policies to reduce the city’s wealth polarisation have been set out, including taxes on banks holding empty properties, free transport passes for those under 16 and a ‘freeze’ on new hotel building. Similar radical democratic constellations are gathering recognition across other parts of Spain, including Madrid’s pluralist platform, Ahora Madrid. Syriza, Greece’s anti-austerity leftist coalition, is also of notable comparison. Much like Take Back the City, these urban groups originated as collaborative ‘spaces’ in which social movements could come together.

Looking forward

Can Amina Gichinga and Take Back the City be London’s Ada Colau and Barcelona en Comú? The latter received robust backing from populist party Podemos, the second largest in Spain, and anti-capitalist, pro-independence party the Popular Unity Candidacy. Take Back the City lacks this official support from within the establishment. However, at a post-Brexit alliance meeting, Gichinga spoke of building a progressive alliance with more established political bodies, like the Green Party and Labour. In turn, the Green Party and Momentum have reportedly shown interest in them.

The group’s post-election online video asserts the importance of “connecting pockets of resistance across our city”. Dalilah proposes that Take Back the City has unique strategic strength due to not being a single issue group, establishing it as a “political arm for the grassroots”. Efforts are thus greatly focussed on collaborating with smaller grassroots groups, like Focus E15 and the Radical Housing Network. Dalilah discusses the significance of a recognised movement that represents London’s cultural and ethnic diversity. At many political events, she reflects, “if we weren’t there, there would be no one like us there”. Of late, the group has been particularly active in speaking to local communities about post-Brexit racism and xenophobia. The expansion of City Airport has too been a major focus, “working with communities to build a cohesive voice” regarding the unjust impacts on local minorities. Potential involvement in a ‘renter’s union’ is also mentioned.

There is no doubt that Brexit Britain’s anti-elitist sentiment makes grassroots urban movements like Take Back the City more relevant than ever. Local activism can rebuild trust outside of central politics, allowing civil societies to realise their collective potential. If only through cementing social ties, these mobilisations can contribute to wider progressive movements. Meanwhile, they help to reconstruct the civic importance of urban space.

We Share Europe: a meeting a Barcelona En Comú

What can urbanists do?

Apparently, urbanists could play an important role in Take Back the City. Dalilah talks of the lacking transparency and accessibility in procedures behind changes to the built environment. Planning processes are especially bureaucratic and complex, working to “keep people out who they don’t want to listen to”, she says. This ‘knowledge gap’ hinders the ability of members to effectively anticipate and campaign against unjust decisions. They therefore want built environment experts to help them with insights, for example which local buildings or public spaces may be under threat, as well as general ‘nitty gritty’ policy knowledge. The group have already collaborated with Just Space, an informal body encouraging public participation in planning, and Land for What, who question the for-profit dominance of land. Interested? Dalilah suggests heading down to the next meeting; your skills and knowledge will no doubt assist the cause.

Tim White is a Young Urbanist and has just completed an MPhil in Planning, Growth and Regeneration at Cambridge University. Motivated by improving socio-spatial equality, his latest research focuses on progressive housing concepts in London.

1. Rebel Cities: From the Right to the City to Urban Revolution, David Harvey, 2012↩

[…] officials follows the model of trying to enact change from the top down. Londoners have made similar points about their mayor, Sadiq Khan. Perhaps these back room conversations could carry more weight […]